How to Build a Cloud-Native Spatial Data Lakehouse

Most spatial workflows today are still running on a foundation of folders, flat files, and fragile scripts. You’ve probably worked with shapefiles stored in six different places, Python notebooks that quietly break when a column changes, and a dozen versions of the same dataset ending in _final_v2_edit.shp. I’ve been there.

But spatial data has changed. It’s bigger, more dynamic, and needs to be accessible across teams and tools. What hasn’t changed fast enough is how we manage it.

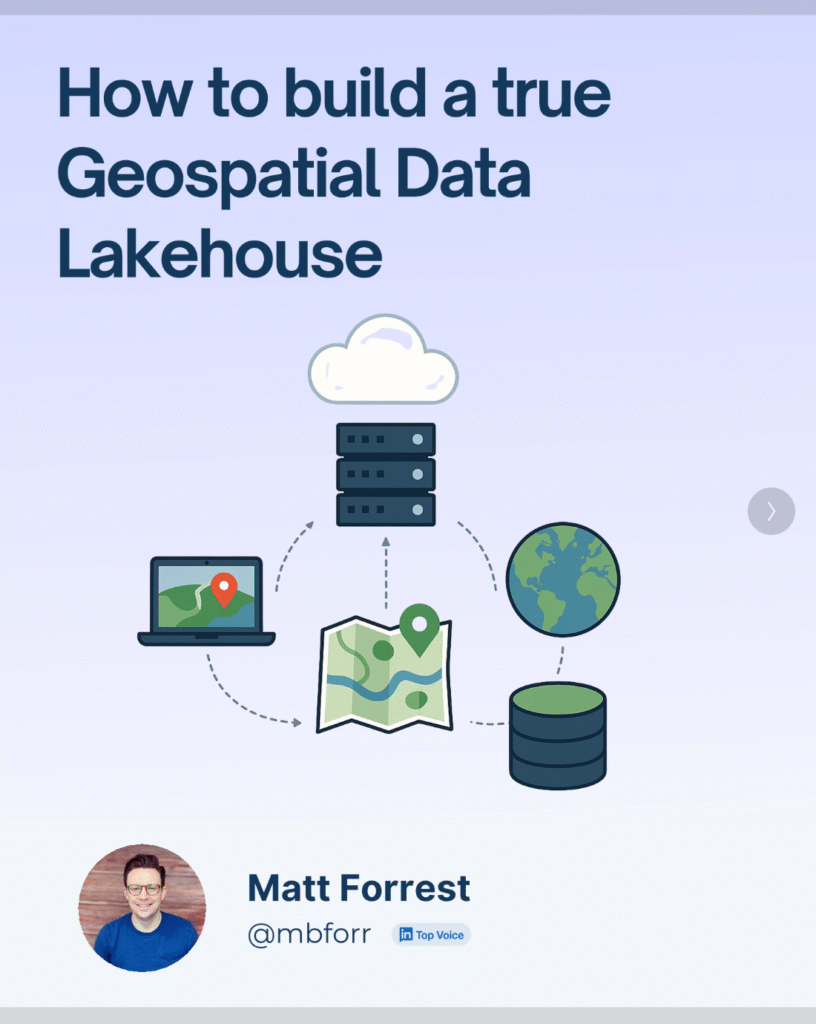

That’s where the spatial data lakehouse comes in.

At its core, a lakehouse architecture combines the flexibility of cloud object storage with the performance and structure of a warehouse. It lets you work with data like an engineer and an analyst—at scale, with full versioning, and without being locked into one platform.

Here’s what you need to build one:

- Cloud-native storage like Amazon S3 or Google Cloud Storage

- Open formats like GeoParquet for vector and COG for raster

- Apache Iceberg as your table format to manage schema, partitioning, and time travel

- Engines like Apache Sedona, Spark, or Wherobots to query your data with SQL

- Airflow to automate ingestion, processing, and updates

This stack doesn’t care what software you use. It’s open, flexible, and built for interoperability. You can load data with Python, query it with SQL, join it across years or sources, and share it across teams without duplicating files or losing control of your schema.

I recently walked through this in a LinkedIn carousel, including how this setup lets you do things like:

- Automatically update a building footprint dataset every month

- Run spatial joins against flood zones without copying files

- Version your tables so you can roll back mistakes

- Build pipelines that scale from your laptop to the cloud

If you’re building anything with geospatial data and you’re tired of managing brittle scripts and bloated folders, this is the architecture you’ve been waiting for.

This isn’t the future of GIS it’s already happening. And it’s time more spatial teams got to work this way.